Ukiyo-e

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For Ukiyo-e Town, see Nura: Rise of the Yokai Clan.

Usually the word ukiyo is literally translated as "floating world" in English, referring to a conception of an evanescent

world, impermanent, fleeting beauty and a realm of entertainments (kabuki, courtesans, geisha) divorced from the

responsibilities of the mundane, everyday world; "pictures of the floating world", i.e. ukiyo-e, are considered a genre

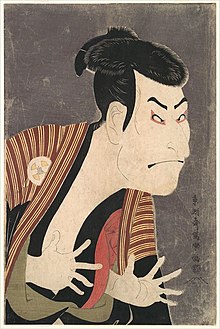

unto themselves.Ukiyo-e (浮世絵 literally "pictures of the floating world") (Japanese pronunciation: [ukijo.e] or [ukijoꜜe])

is a genre of Japanesewoodblock prints (or woodcuts) and paintings produced between the 17th and the 20th centuries,

featuring motifs of landscapes, tales from history, the theatre, and pleasure quarters. It is the main artistic genre of

woodblock printing in Japan.

The contemporary novelist Asai Ryōi, in his Ukiyo monogatari (浮世物語 "Tales of the Floating World", c. 1661),

provides some insight into the concept of the floating world:

provides some insight into the concept of the floating world:

... Living only for the moment, turning our full attention to the pleasures of the moon, the snow, the cherry

blossoms and the maple leaves; singing songs, drinking wine, diverting ourselves in just floating, floating;

... refusing to be disheartened, like a gourd floating along with the river current: this is what we call the floating

world...[1]

View of Mount Fuji from Harajuku, part of the

Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō series by Hiroshige, published 1850

The art form rose to great popularity in the metropolitan culture of Edo (Tokyo) during the second half of the 17th century, originating with the single-color works of Hishikawa Moronobu in the 1670s. At first, only India ink was used, then some prints were manually colored with a brush, but in the 18th century Suzuki Harunobu developed the technique of polychrome printing to produce nishiki-e.

Ukiyo-e were affordable because they could be mass-produced. They were mainly meant for townsmen, who were generally not wealthy enough to afford an original painting. The original subject of ukiyo-e was city life, in particular activities and scenes from the entertainment district. Beautiful courtesans, bulky sumo wrestlers and popular actors would be portrayed while engaged in appealing activities. Later on landscapes also became popular. Political subjects, and individuals above the lowest strata of society (courtesans, wrestlers and actors) were not sanctioned in these prints and very rarely appeared. Sex was not a sanctioned subject either, but continually appeared in ukiyo-e prints. Artists and publishers were sometimes punished for creating these sexually explicit shunga.

Contents[hide] |

[edit]History

Ukiyo-e can be categorized into two periods: the Edo period, which comprises ukiyo-e from its origins in the 1620s until about 1867, when the Meiji period began, lasting until 1912. The Edo period was largely a period of calm that provided an ideal environment for the development of the art in a commercial form; while the Meiji period is characterized by new influences as Japan opened up to the West.

The roots of ukiyo-e can be traced to the urbanization that took place in the late 16th century that led to the development of a class of merchants and artisans who began writing stories or novels, and painting pictures, compiled in ehon (絵本, picture books, books with stories and picture illustrations), such as the 1608 edition of Tales of Ise by Hon'ami Kōetsu. Ukiyo-e were often used for illustrations in these books, but came into their own as single-sheet prints (e.g., postcards or kakemono-e) or were posters for the kabuki theater. Many stories were based on urban life and culture; guidebooks were also popular; and all in all had a commercial nature and were widely available. Hishikawa Moronobu, who already used polychrome painting, became very influential after the 1670s.

In the mid-18th century, techniques allowed for production of full-color prints, called nishiki-e, and the ukiyo-e that are reproduced today on postcards and calendars date from this period on. Utamaro, Hokusai, Hiroshige, and Sharaku were the prominent artists of this period. After studying European artwork, receding perspective entered the pictures and other ideas were picked up. Katsushika Hokusai's pictures depicted mostly landscapes and nature. His Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (富嶽三十六景 Fugaku sanjūrokkei) were published starting around 1831. Ando Hiroshige and Kunisada also published many pictures drawn on motifs from nature.

In 1842, pictures of courtesans, geisha and actors (e.g., onnagata) were banned as part of the Tenpō reforms. Pictures with these motifs experienced some revival when they were permitted again.

During the Kaei era, (1848–1854), many foreign merchant ships came to Japan. The ukiyo-e of that time reflect the cultural changes.

Following the Meiji Restoration in 1868, Japan became open to imports from the West, including photography, which largely replaced ukiyo-e during the bunmei-kaika (文明開化, Japan's Westernization movement during the early Meiji period). Ukiyo-e fell so far out of fashion that the prints, now practically worthless, were used as packing material for trade goods. When Europeans saw them, however, they became a major source of inspiration for Impressionist, Cubist, and Post-Impressionist artists, such as Vincent van Gogh, James Abbott McNeill Whistler,Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Mary Cassatt, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and others. This influence has been called Japonisme. The prints also influenced early Modernist poetry in many important ways, with Imagist poets such as Ezra Pound, Richard Aldington and Amy Lowellallowing them strongly to influence their imagery and aesthetic sentiments.[2][3]

Though ukiyo-e saw its end in the Meiji period, and the term is not applied to works after that time, in the 20th century, during the Taishō andShōwa periods, new print forms arose in Japan. The shin hanga ("New Prints") movement, a print equivalent to the Nihonga movement in painting, drew upon ukiyo-e traditions, creating images of traditional Japanese scenes, in traditional modes and forms. Inspired by EuropeanImpressionism, the artists incorporated Western elements such as the effects of light and the expression of individual moods but focused on strictly traditional themes. The major publisher was Watanabe Shozaburo, who is credited with creating the movement. Important artists included Itō Shinsui and Kawase Hasui, who were named Living National Treasures by the Japanese government. Shin hanga was particularly popular among Western collectors, who enjoyed images of traditional Japan and mourned its loss, as Japan pressed forward with modernization and Westernization campaigns.

The less-well-known sōsaku hanga movement, literally creative prints, followed a Western concept of what art should be: the product of the creativity of the artists, creativity over artisanship. Traditionally, the processes of making ukiyo-e — the design, carving, printing, and publishing — were separated and done by different and highly specialized people (as was also traditionally the case with Western woodcuts). Sōsaku hanga advocated that the artist should be involved in all stages of production. The movement was formally established with the formation of the Japanese Creative Print Society in 1918, however, it was commercially less successful, as Western collectors preferred the more traditionally Japanese look of shin hanga.

[edit]Making of ukiyo-e

Ukiyo-e prints were made using the following procedure:

- The artist produced a master drawing in ink

- An assistant, called a hikkō, would then create a tracing (hanshita) of the master

- Craftsmen glued the hanshita face-down to a block of wood and cut away the areas where the paper was white. This left the drawing, in reverse, as a relief print on the block, but destroyed the hanshita.

- This block was inked and printed, making near-exact copies of the original drawing.

- A first test copy, called a kyōgo-zuri, would be given to the artist for a final check.

- The prints were in turn glued, face-down, to blocks and those areas of the design which were to be printed in a particular color were left in relief. Each of these blocks printed at least one color in the final design.

- The resulting set of woodblocks were inked in different colors and sequentially impressed onto paper. The final print bore the impressions of each of the blocks, some printed more than once to obtain just the right depth of color.

[edit]Important artists

- Hishikawa Moronobu (1618–1694)

- Torii Kiyonobu I (c.1664–1729)

- Suzuki Harunobu (1724–1770)

- Torii Kiyonaga (1752–1817)

- Utamaro (ca. 1753–1806)

- Sharaku (active 1794–1795)

- Hokusai (1760–1849)

- Toyokuni (1769–1825)

- Keisai Eisen (1790–1848)

- Kunisada (1786–1865)

- Hiroshige (1797–1858)

- Kuniyoshi (1797–1861)

- Kunichika (1835–1900)

- Chikanobu (1838–1912)

- Yoshitoshi (1839–1892)

- Ogata Gekko (1859–1920)

[edit]See also

[edit]Notes

- ^ Lane, Richard. Images from the Floating World. Old Saybrook, CT: Konecky & Konecky, 1978. p11.

- ^ Arrowsmith, Rupert Richard. Modernism and the Museum: Asian, African and Pacific Art and the London Avant Garde. Oxford University Press, 2011, passim. ISBN 978-0-19-959369-9

- Also see Arrowsmith, Rupert Richard. "The Transcultural Roots of Modernism: Imagist Poetry, Japanese Visual Culture, and the Western Museum System", Modernism/modernity Volume 18, Number 1, January 2011, 27-42. ISSN: 1071-6068.

- ^ Video of a Lecture discussing the importance of Japanese prints to Global Modernism, School of Advanced Study, July 2011.

[edit]References

- Forrer, Matthi, Willem R. van Gulik, Jack Hillier A Sheaf of Japanese Papers, The Hague, Society for Japanese Arts and Crafts, 1979. ISBN 90-70265-71-0

- Kaempfer, H. M. (ed.), Ukiyo-e Studies and Pleasures, A Collection of Essays on the Art of Japanese Prints, The Hague, Society for Japanese Arts and Crafts, 1978. ISBN 90-70216-01-9

- Lambourne, Lionel. Japonisme: Cultural Crossings Between Japan and the West. London, New York: Phaidon Press, 2005. ISBN 0-7148-4105-6

- Lane, Richard. (1978). Images from the Floating World, The Japanese Print. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 10-ISBN 0192114476/13-ISBN 9780192114471; OCLC 5246796

- Friese, Gordon. Hori-shi. 249 facsimiles of different seals from 96 Japanese engravers. Unna: Verlag im bücherzentrum, 2008.

- Newland, Amy Reigle. (2005). Hotei Encyclopedia of Japanese Woodblock Prints. Amsterdam: Hotei. 10-ISBN 9074822657/13-ISBN 9789074822657; OCLC 61666175

- Roni Uever, Susugu Yoshida (1991) Ukiyo-E: 250 Years of Japanese Art, Gallery Books, 1991, ISBN 0-8317-9041-5

- Yamada, Chisaburah F. Dialogue in Art: Japan and the West. Tokyo, New York: Kodansha International Ltd., 1976. ISBN 0-87011-214-7

[edit]Further reading

- Penkoff, Ronald. (1964). Roots of the Ukiyo-e; Early Woodcuts of the Floating World.

[edit]External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Ukiyo-e |

- A Guide to the Ukiyo-e Sites of the Internet

- Ukiyo-e in "History of Art"

- History of Ukiyoe

- Ukiyoe collection from Edo-Tokyo Museum

- Kuniyoshi Project

- Gallery with a lot of info

- Overviews of the Printmaking Process detailed description of the stages of printmaking with many illustrations

- Viewing Japanese Prints

- Ukiyo-e at JAANUS (Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System)

- What is a Print? An excellent flash-demonstration of the printmaking process

- Minneapolis Institute of Arts; Video: Pictures of the Floating World

- Universes in Collision: Men and Women in Nineteenth Century Japanese Prints

- Hokusai Online Exhibition; Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

- The Floating World of Ukiyo-e, Library of Congress exhibition

- Ukiyo-e Techniques, an interactive collection of videos and animations demonstrating the techniques of master printmaker Keiji Shinohara.

- Ukiyo-e Caricatures 1842-1905 Database of the Department of East Asian Studies of the University of Vienna

- Japanese Erotic Art in the "History of Art"

- Biographies of over 100 Japanese print-making artists